Thanks to thousands of informal workers, SA already does pretty well with recycling paper and aluminium but could do far more with plastics, where there’s a particular problem

When it comes to generating waste, SA is among the worst offenders, ranking 15th by volume globally, according to the World Bank. A key part of the solution to the 50Mt a year problem lies in recycling, a field in which SA excels in some areas but lags behind badly in others.

The paper industry has shown what can be achieved, having last year recycled 70% of the 1.8Mt of waste-paper materials spewed out primarily by the consumer sector. It was a target set by the Paper Recycling Association of SA to be reached in 2020, with the 1.3Mt recycled being enough to fill 1,539 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

“SA’s 70% recycling rate is similar to levels achieved in Europe,” says John Hunt, MD of Mpact’s recycling division, which procures more than 660,000t annually for use in the group’s three carton-board mills.

To move much beyond a 70% recycling rate is a big ask, says Hunt. The challenge is to collect more discarded paper material from households. “People know it’s the right thing to do but it needs to be made more convenient,” says Hunt. “We need the intervention of municipalities.”

Mpact has already shown what can be achieved. Working with three Gauteng municipalities — Johannesburg, Ekurhuleni and Tshwane — it makes scheduled kerbside pickups from 200,000 households.

Another big recycling success has been achieved by the metals packaging sector which, according to industry body MetPac-SA, achieved a 73% recycling rate in 2017. This was up from just 17% 20 years earlier, with a 75% rate targeted by 2021.

The newcomer to the metals packaging scene is aluminium, thanks to a wholesale shift from steel cans by SA Breweries and Coca-Cola. It has created a major recycling opportunity for aluminium company Hulamin. “We invested R300m in a recycling plant,” says Clayton Fisher, Hulamin’s strategy & supply chain group executive.

The plant commissioned in 2015 is ramping up to full capacity, which will meet 20% of SA’s aluminium can needs, says Fisher.

The recycling rate for aluminium cans has reached 75% but should go far higher. “In Brazil, 95% of aluminium cans are recycled,” he says.

The big incentive is high prices for aluminium scrap. “Collectors receive R5-R10 a kilogram, which is far higher than for steel cans,” says Fisher.

Seemingly not as successful at recycling is the plastics industry, which in 2017 recycled 334,727t, a recycling rate of just 43.7%. It could be far higher if not for one problem.

“There is an oversupply of reclaimed material in virtually all plastics sectors,” says Douw Steyn, a director of industry body Plastics SA. “We need to create new markets for recycled plastics.”

One possible new market is conversion of certain plastics into diesel. It is already being done commercially in a number of countries, including the US, Spain and Australia.

Large-scale recycling in SA is made possible by the thousands of women and men who scour landfills or pound city streets with trolleys in their quest for recyclable waste.

While an exact number of people involved is unavailable, Mpact puts the number of primarily informal workers in the paper sector at about 100,000. Plastics SA puts the number of workers in its sector at 57,600.

There is still scope to create many more jobs, not least in the neglected electronic waste (e-waste) sector.

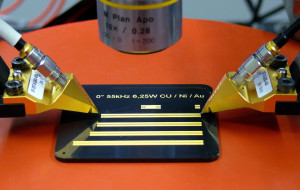

“E-waste encompasses all electronic devices, electrical appliances and batteries,” says Keith Anderson, CEO of the e-Waste Association of SA. “At present SA is recycling only about 6%-9% of e-waste generated.”

E-waste also represents the fastest-growing waste sector. “SA is generating 6kg of e-waste per person every year and it’s a figure growing at 5% annually,” says Anderson.

A 2017 study by research organisation Mintek put the volume of e-waste being recycled in SA in 2015, by the 18 largest companies involved, at only 17,773t. It indicates that upwards of 280,000t of e-waste generated annually ends up in landfills.

This represents a hazard, with many electronic devices containing potentially harmful components such as lead, cadmium, beryllium and brominated flame retardants.

Even batteries are potentially harmful when their casings disintegrate and leak lead, lithium, mercury and nickel.

Anderson says something that increases the risk of pollution is that many landfill sites are near rivers.

Though not all waste material that ends up in landfills can be recycled, more can certainly be done. Government is determined to make it happen.

The national pricing strategy for waste management will lay out legislation to penalise companies and organisations failing to meet minimum recycling requirements.

Source : businesslive.co.za