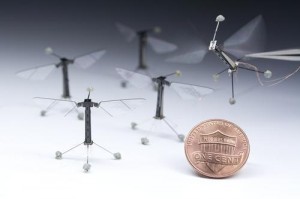

After 10 years of hard work, an engineering team working in Harvard University’s Microrobotics Lab has completed the maiden flight of its tiny RoboBee flying robot. True, the little guy is still tethered and not autonomous yet, but the controlled flight of the insect-sized robot that flaps its wings is considered a first in robotics.

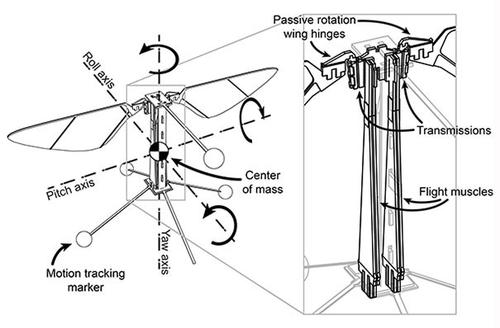

The tiny robot weighs 80 mg (0.002 oz), has a wingspan of 3 cm (1.18 inch), and a body frame made of carbon fiber. It beats its independently controlled wings, which are actuated via piezoelectricity, 120 times per second. Power and control signals are sent through the tether to the robot. In the video below, you can watch the robotic bee’s flight in the laboratory’s motion capture environment. It’s shown hovering and moving laterally.

Flying robots that flap their wings, like Festo’s partially autonomous SmartBird or MIT’s remote-controlled Phoenix, can be harder to design and actuate than robots with fixed wings that soar or quadrotors that hover. Part of the challenge is in controlling the robot’s movements, since flapping wings’ movements are much more complex than gliding wings’ movements. Flapping wings also have more of an effect on the twisting and turning of the robot’s body.

Independent control of each wing — such as Festo has achieved with its highly sophisticated, four-winged BionicOpter dragonfly robot — makes it easier to control the robot’s flight. But the RoboBee is made at such a small scale that tiny changes in air movement can have an even larger effect on the robot’s flight dynamics and its rotational movements. That meant the team had to design a control system with very fast reaction times.

Another major challenge for the Harvard team was in finding components and materials small enough for a robot that’s not much bigger than a quarter. Flight muscles and actuators, such as electromagnetic motors, are much easier to come by for larger flying robots.

The RoboBee’s piezoelectric actuators are tiny strips of ceramic material that expand or contract in response to the application of electricity. Its joints are thin plastic hinges embedded in its body frame. The reason the RoboBee is still on a tether also has to do with its size: there are no energy storage devices small enough, such as fuel cells with high energy densities, at least not yet.

The team was inspired to develop the RoboBee’s body and movements by those of a fly: it can take off vertically and hover. However, the RoboBee project, led by Robert J. Wood — professor at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), a Core Faculty Member at Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, and founder of the Microrobotics Lab — is aimed at creating fully autonomous robotic swarms. Possible uses will include search and rescue, pollination of agriculture crops, and distributed environmental monitoring.

The team published its findings in an article (purchase or subscription only) in Science magazine. Graduate students Pakpong Chirarattananon and Kevin Y. Ma are co-lead authors, and the third author is Sawyer B. Fuller, a postdoctoral researcher. The research received funding from the Wyss Institute and the National Science Foundation.

Source: http://www.designnews.com/author.asp?section_id=1386&doc_id=264095&itc=dn_analysis_element&